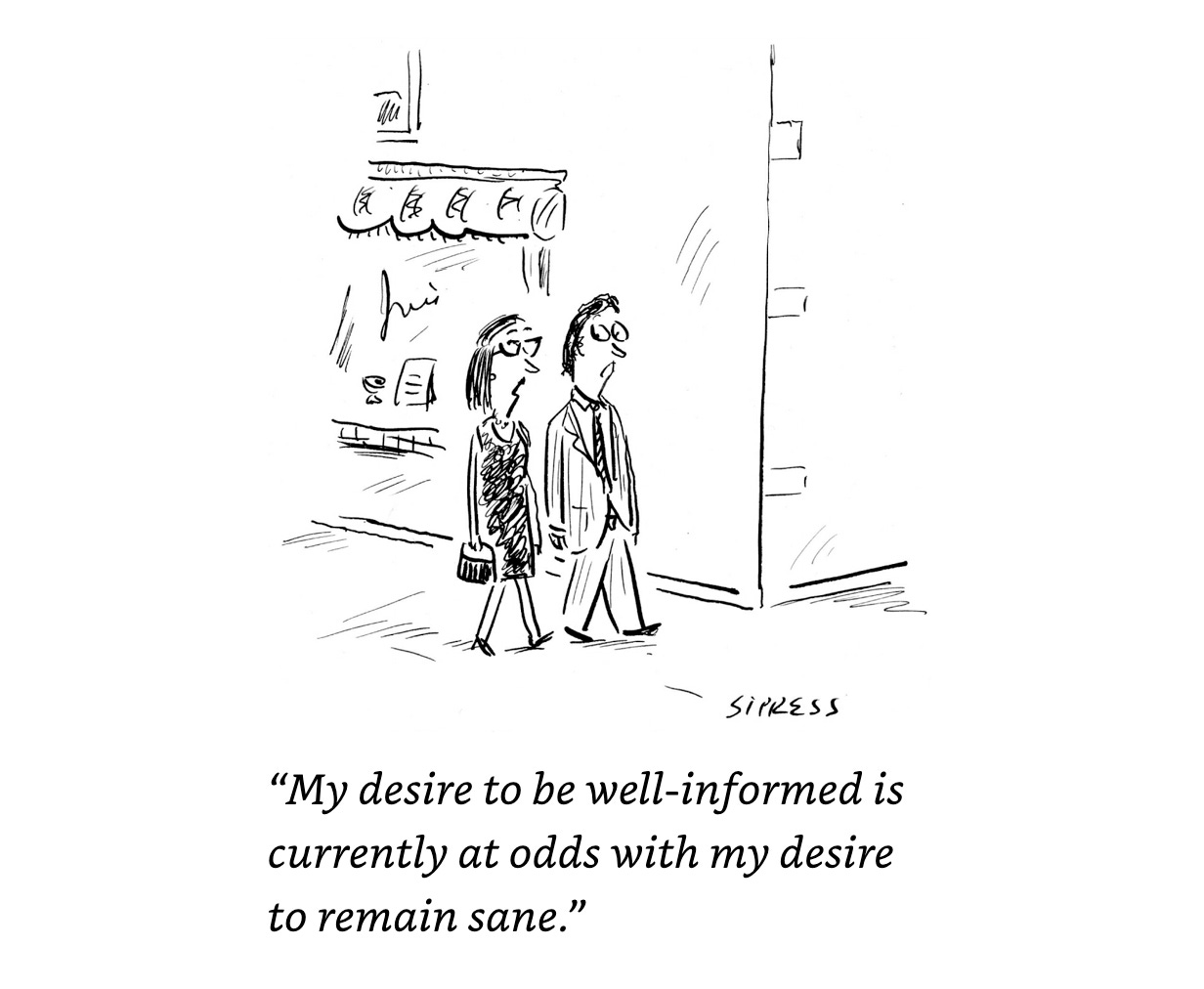

Every morning, before I even rise from my bed, I open the BBC News app on my phone. Laying there, blinking in the too-bright light from the small screen, feels like a solemn responsibility. I am called to bear witness to the neverending outrages, horrors, disasters and foolishness that happened while I slept.

It’s a crappy way to start the day.

My phone could probably tell me how many hours (days?) a month I spend doomscrolling through news reports, LinkedIn posts about that news, deep dives into the background, scathing opinions and data analysis of it all. Catastrophic headlines ping onto my screen by the minute, algorithms funnelling my attention toward the worst-case scenarios. It’s literally my job to ‘stay up to date’ on news about climate change and sustainability. And I scour all that information, opinion and data for scraps of solutions and strategies for action.

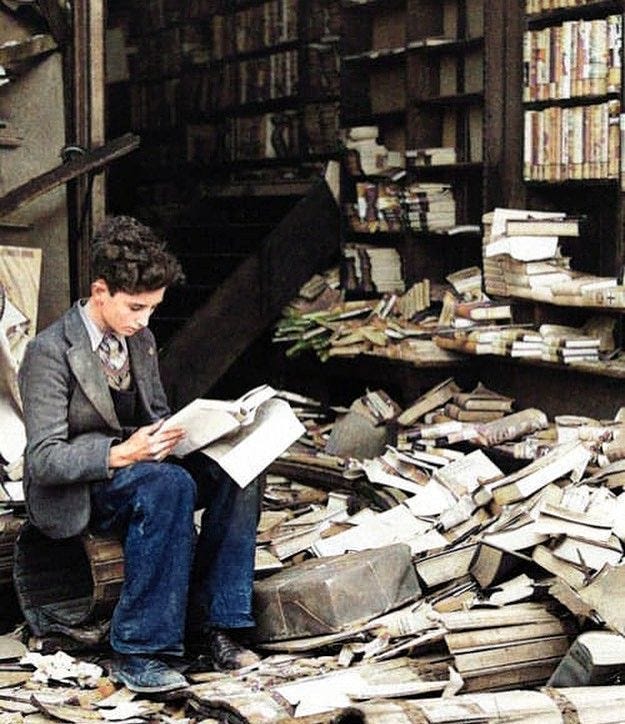

Then, almost shamefully, as if partaking in an indulgence that betrays the suffering in all that reality, I read a novel or watch a movie in the evening. I come here on Substack to hurriedly gulp down a short story. Or even, heaven forfend, I daydream my own little fictional vignettes, plotting out my next novel.

The Science Of Fiction

But what if those stories offer more than escapism? Perhaps it’s those dramas, romances, fantasies and thrillers that fuel my resilience, emotional dexterity, and, ultimately, hope.

Last week, I wrote that creative people tend to be more optimistic about our future -because imagination is necessary to conjure pathways out of disasters. And the more creative you are, the more solutions you can invent.

And creativity doesn’t (only) mean sitting at a desk pounding out an 80,000-word novel.

Reading a novel or short story, watching a movie or play, or even playing princesses or astronauts with your kids demands imagination - and that’s the raw material with which we build hope.

It may seem counterintuitive. After all, fiction is almost always centred on conflict, jeopardy, or heartbreak. The much-followed structure of the ‘Hero’s Journey’ story arc literally requires a writer to take their character out of everyday reality and fling them into ever more emotionally and/or physically perilous scenarios. Yet, this very aspect is what makes it a vital tool for emotional strength. According to research from the University of Toronto, reading fiction measurably grows our empathy and emotional intelligence. By stepping into the minds and hearts of characters in these overwhelming situations, we practice our own emotional responses to complexity and uncertainty - skills sorely needed in our real-world lives.

One of my favourite genres is science fiction. Perhaps I won’t ever face a galactic war, terraform a far-off planet, or fall in love with an artificial intelligence. But the emotional upheaval of these imagined futures maps onto my real and often justified fears: loss, survival, identity, and the unknown. These narratives offer a safe space to experience terror and triumph without the real-world consequences. In doing so, they offer a rehearsal of resilience. Margaret Atwood has long said that dystopias are not predictions but warnings - and with each warning comes the possibility of change. Through fictional futures, we learn that chaos is survivable, solutions are possible, and endurance is always part of the story.

Empathy Training

Research supports this emotional training ground of fiction. Psychologist Keith Oatley highlights how stories function as a flight simulator for the mind, where we can practice social and emotional strategies in a controlled setting. We absorb the characters’ coping mechanisms and resourcefulness that then imprint on our subconscious. When you find the inner strength to deal with the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, that fortitude may have been planted there by a story you read as a teenager.

This revelation echoes findings by neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf, who writes in the wonderful book Reader Come Home that consuming fiction strengthens our ‘cognitive patience’ and raises our capacity for reflection - exactly the mental attributes that all my doomscrolling erodes.

A few weeks ago I explained why Lord of the Rings is my favourite climate fiction. J.R.R. Tolkien also coined one of my most beloved terms: ‘eucatastrophe’, which is a massive turn in fortune from a seemingly unconquerable situation to an unforeseen victory.

Eucatastrophe is the moment when Sauron’s giant hand is revealed to be nothing more than smoke, and Gandalf celebrates the great triumph of the gathered allies, who had all ridden out to war girded for their destruction. Or Shakespeare’s Henry V on the battlefield of Agincourt, having faced French troops outnumbering his own sickly and bedraggled followers, who asks, ‘I tell thee truly, herald, I know not if the day be ours or no’ after his resounding victory.

Fiction trains us to expect these turns, to anticipate that within difficulty lies the possibility of grace. This is not naïve optimism; it’s a disciplined belief that hardship can lead to transformation. Eucatastrophe is possible for us all - if we give everything against the odds.

To Change The Future, We Must Imagine A Better One

There’s a reason why speculative fiction is often at the forefront of social change. From Octavia Butler’s prescient visions of climate crisis and inequality to Ursula K. Le Guin’s explorations of anarchism and gender, fiction doesn’t just reflect reality - it exponentially expands it. When the real world feels stuck, fiction reminds us that new pathways are possible.

Several years ago, feeling overwhelmed by the seemingly intractable political and industrial causes of climate change, I daydreamed about a world that had it worse than us. Without climate science, this world blames worsening weather on capricious gods, and without renewable energy, the fossil fuel system is literally the only way to keep the lights on. This playful mind game became the basic framework for my upcoming novel GODSTORM. I discovered, to my joy, that dreaming up answers in this fictional world made solutions in our reality suddenly feel much more possible.

So, in an era of relentless fear and crisis, fiction is more than a retreat; it’s an act of mental fortification. It trains us to hold complexity, to face our fears without being consumed by them, and to imagine solutions beyond the current narrative.

So the next time my news feeds feel unbearable, I’ll close my browser and open a book (or write another one). Doomscrolling feeds anxiety. Fiction feeds hope - not by sugar-coating reality, but by helping us confront it with courage and imagination.

If today’s offers you too much reality to handle, turn to fiction for solutions.

[Please share this post on Linkedin and other social media with friends who might need this permission to let fiction fuel their hope]

So glad to see another optimistic climate novel coming! For a while, Steve and I were feeling very lonely. Our book, Fairhaven - A Novel of Climate Optimism, is usually paired with Ministry for the Future by KSR, which is great of course, but the latter is a very grim read. Looking forward to seeing more from you! https://habitatpress.com/fairhaven/

So on point, Solitaire 👏 can’t wait to read Godstorm as well.

As someone who’s been converted to this school of thought, I’ve been grappling with another question: which sci-fi should we be reading and prioritising today?

I’ve been jamming with the idea of a 2x2 matrix that maps sci-fi along a 'dystopian vs. utopian' axis, and a 'normalising vs. critical' axis. I thought this framework would be a useful way to distinguish between dystopias that collapse into doom-porn vs. those that imagine resistance and reform, and ‘lazy’ utopias that feel like complacent fantasies, vs. those that offer practical imagination (e.g. the ambiguous utopia).

It also acknowledges the merits of different sub-genres of sci-fi, like cli-fi but also those speculative works focused on justice, power and identity, like Le Guin's work.

Would love to know what you think of this framework.